by Dick Bourne

Mid-Atlantic Gateway

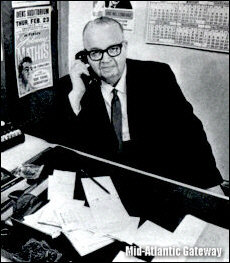

While doing research for a future article on Jim Crockett, Sr., and the origins of local TV wrestling for Jim Crockett Promotions, I came across the following tribute written by Bob Quincy and published on page 20 in the Charlotte Observer on the afternoon of April 3, 1973. Jim Crockett, Sr., had died just two days earlier.

It's a wonderful tribute written with great affection and respect for the man who redefined event promotion in the Queen City (as well as all the Carolinas and Virginia) for nearly four decades.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

THE PROMOTER

by Bob Quincy

Charlotte Observer, Charlotte, NC - April 3, 1973

He would survey an arena with eyes scanning like a radar scope. The blips indicated empty seats. Vacancy was a nasty word to Jim Crockett.

"It's raining up the road," a confederate would console. "Some of these people in the mills don't get their payday this week."

Jim, after his hasty count of the house. would shake his head sadly and say, "We didn't give them what they wanted. The people come when you give them what they want."

He was a man of few words, a paradox as a highly successful promoter. He shunned fanfare. His office was as unpretentious as a janitor's closet in low rent apartment. Crockett had the size of two pro tackles welded together, but he was impeccably neat in his dress. Dark blue was his favorite color.

A call to Jim Crockett usually resulted in Jim Crockett answering the telephone. He ran a million-dollar business off the top of his head and without a secretary. Wrestling tonight, Victor Borge tomorrow, followed by the Harlem Globetrotters.

Crockett died this week at 64. He was a remarkable man.

Wrestling And Big Bands

It began in the early 1930s when Jim was seeking a business and Charlotte was hoping to find that rarest of individuals, an honest wrestling promoter. Crockett came into the city with very little money, a clean-cut Virginia face and a pledge to offer a fair count and an honest billboard.

So he became THE promoter. It wasn't a business like IBM but it rallied its weekly faithful and each year it grew. The names changed but the faces were the same. The good and the bad and the ugly. The bad and the ugly often drew better than the good. They still talk about Cowboy Luttrell as the king of the rat pack.

Jim Crockett got his footing and once his head was above water, he tried a bit of everything. He began dealing in the big band business and his dance nights filled the old Armory. He was on first-name terms with the Dorsey brothers, Stan Kenton, Ben Bernie, and the ageless Mr. Lombardo.

Satchmo Armstrong called him Big Jim. Jack Dempsey wrapped an arm around his thick shoulders. Joe Louis referred to him as "a great man." Ray Charles gave Crockett some headaches and full houses.

No Fat-Cat Looks

Jim had a friend in Gene Autry, the Western star, and James Brown, the singer. He often booked shows he knew were bad business to do a friend a favor — realizing he might be on the hook sometime. He would sit off-stage and monitor a performance. It was his personal thrill.

Crockett drove comfortable automobiles, but he would pale at the sight of a Cadillac salesman. He'd explain, “It's a great car but I don't want my customers to see me driving to the show looking like a fat cat. Not when they're having problems digging up $1.50 for a balcony seat."

He lived in the same home for 25 years until his children were grown and he could relax a bit. He then built a handsome residence. He occasionally took trips, but his vacation time was the only slim thing about him. In recent year he had visited Europe and Japan. Jim's real joy was his wife and his business.

He was a big man, but few people called him fat. Maybe he weighed 350 or 400 pounds at one time. He wouldn't have been Jim Crockett had he worn a Ray Bolger body. He once went on a strict diet, lost 100 pounds and the mirror still wasn't flattering. Jim said to hell with starvation after that ordeal.

Honesty And Hard Work

Some years ago, he was convinced that televised wrestling would stimulate business. He began screening his gladiators weekly and the ratings zoomed at the station. So did his live box office.

A Crockett diary would fill a bookcase on show business dates. He presented ice shows and boxing bouts and fishing tournaments and the roller derby. He offered a bear that wrestled and a boxing kangaroo. It was the Crockett touch that brought "My Fair Lady" to Ovens Auditorium as an artistic success.

"I've never seen a better dressed or more appreciative audience," Jim told Paul Buck. "I've never made less money for the work. Shows price themselves out of business. So do many of the name stars."

The Crockett empire grew on hard business facts, an ear to the public pulse and a baker's honesty. Said Jim: "If you promise them Andy Williams for two hours, make sure Andy's out there early and see that he doesn't leave for 122 minutes."

Jim hadn't been feeling well. Last Friday morning he found it difficult to breathe. Mrs. Crockett got him to the hospital and his sizable family couldn't hide its concern. In the emergency room, he called to John Ringley, his son-in-law, and whispered, "Look after them."

Jim Crockett had seen too many curtains fall not to recognize his own.

* * * * * *

Bob Quincy was known affectionately as "the Dean of North Carolina sportswriters." Named five times as North Carolina Sportswriter of the Year, he had a distinguished career in journalism that included sports editor for the Charlotte News, sports information director for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, radio and television staff at WBT/WBTV, and most famously as a popular columnist for the Charlotte Observer from 1971 up until the time of his death in 1984.

From the Mid-Atlantic Gateway Archives at MidAtlanticWrestling.net